A collaboration between Beatrice Updegraff and Jaipur Rug Foundation

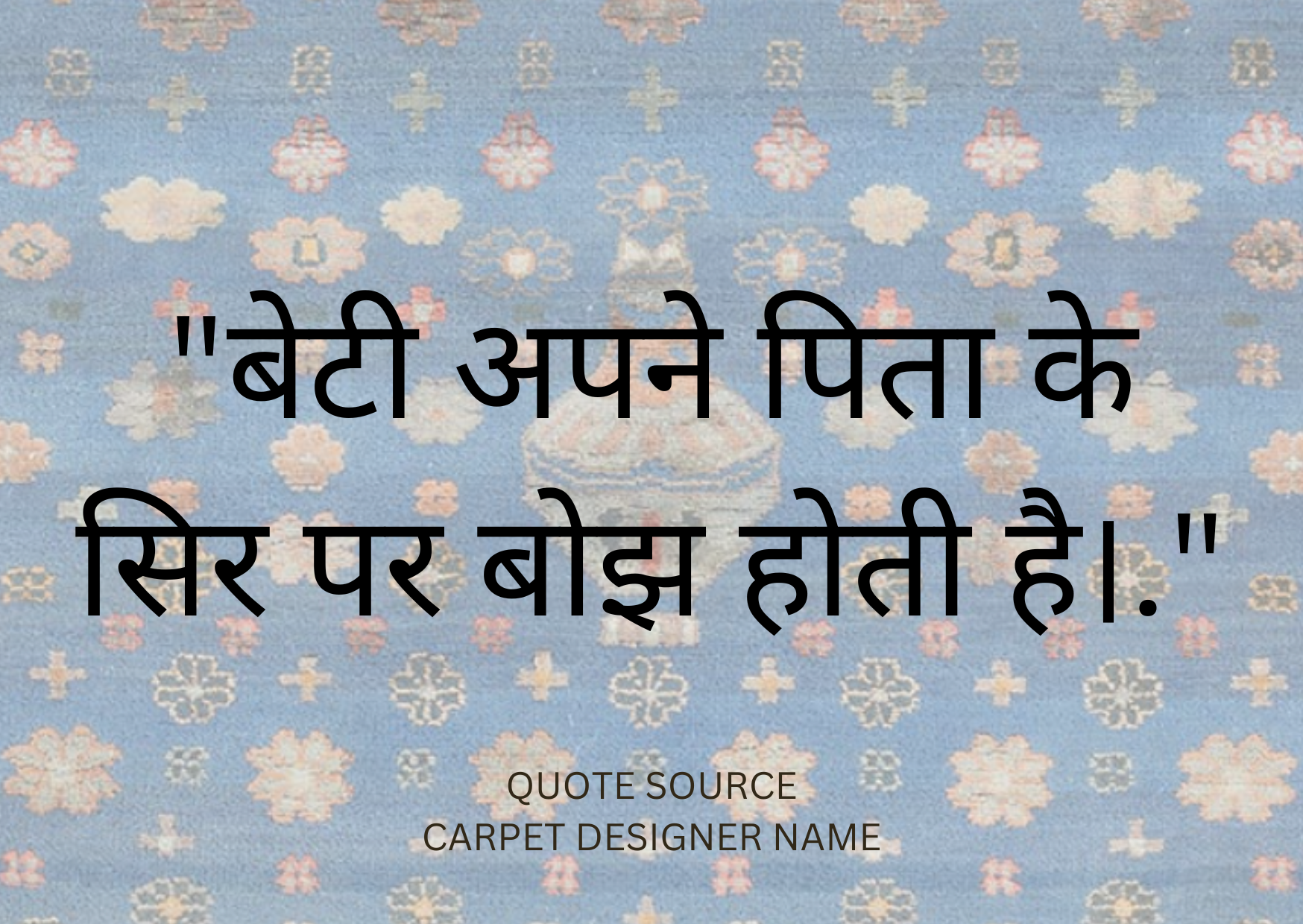

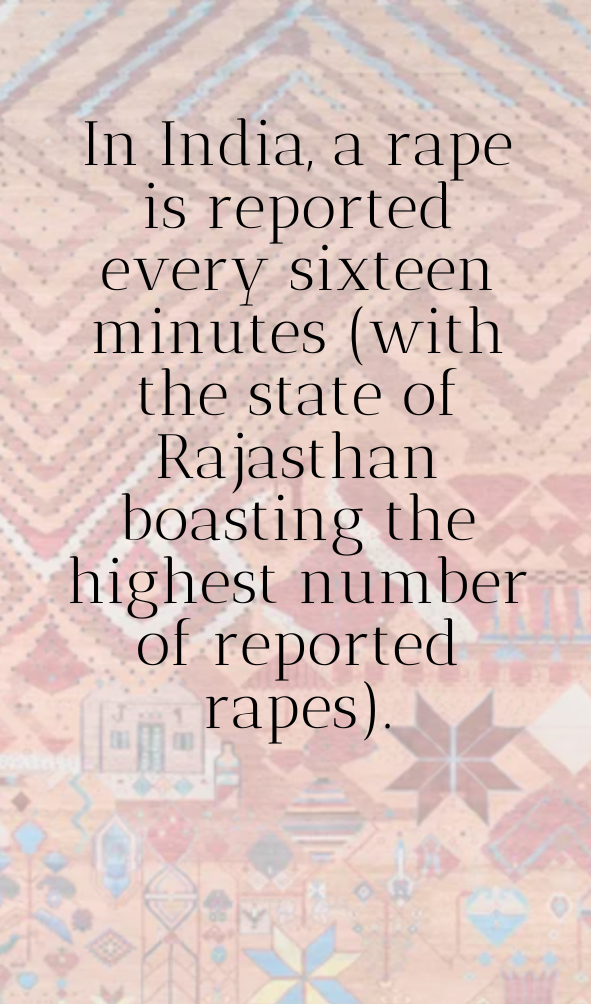

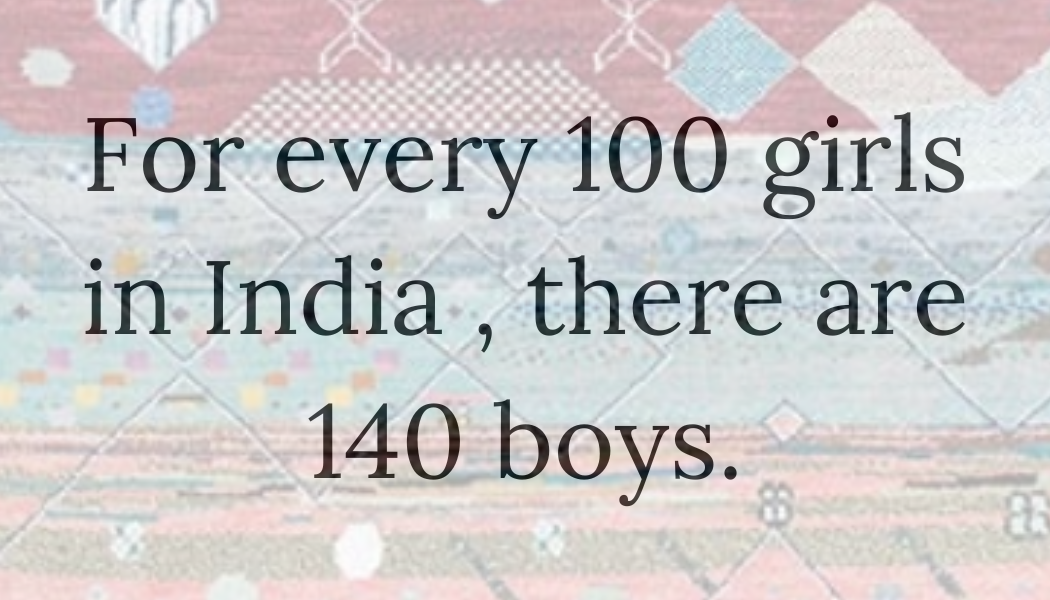

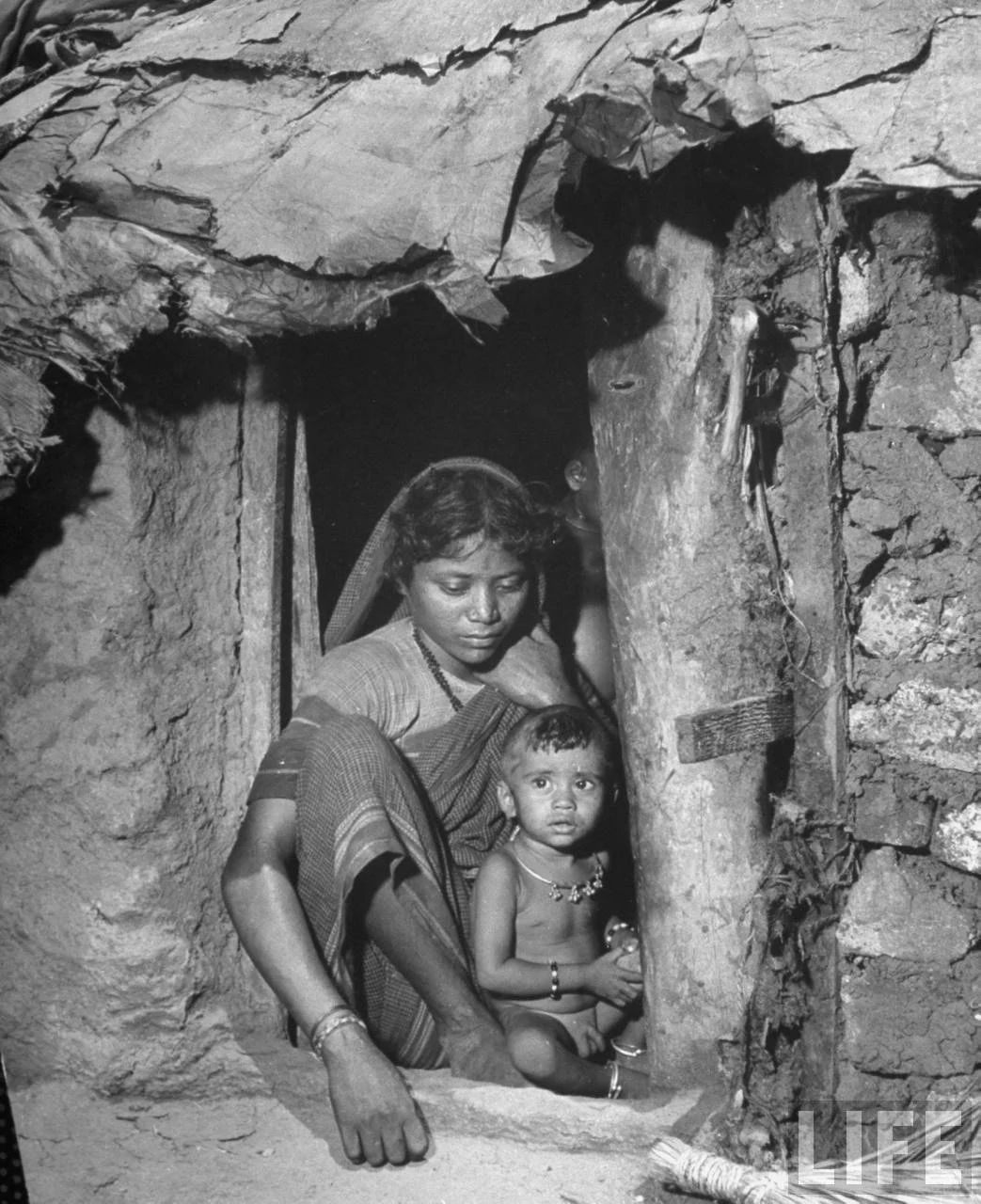

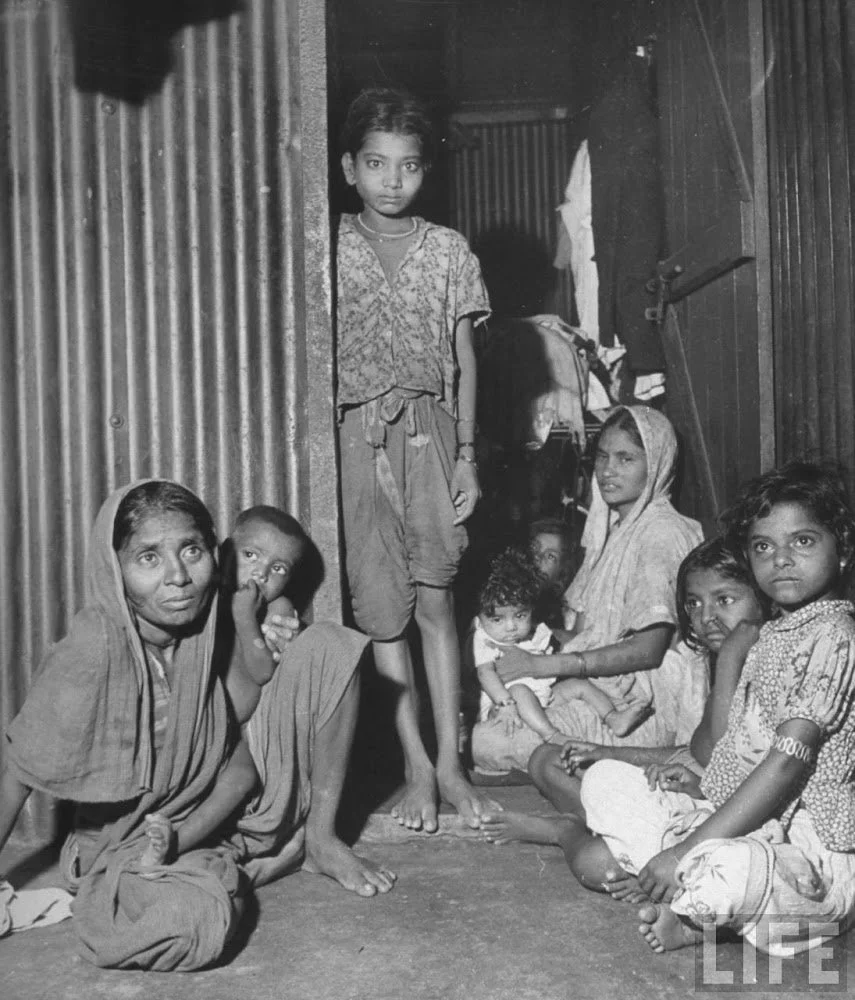

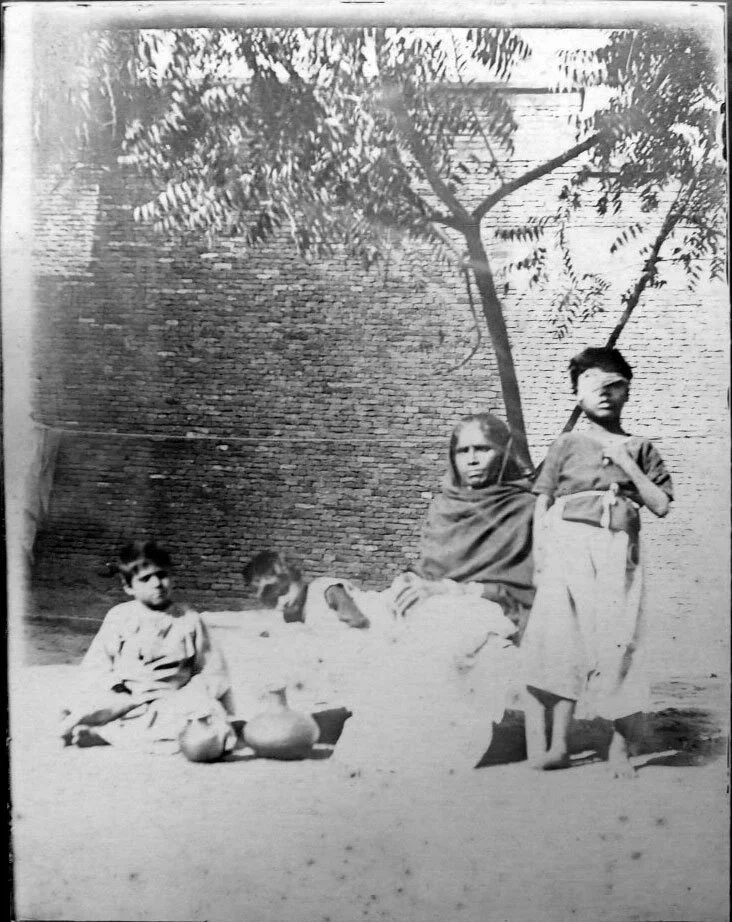

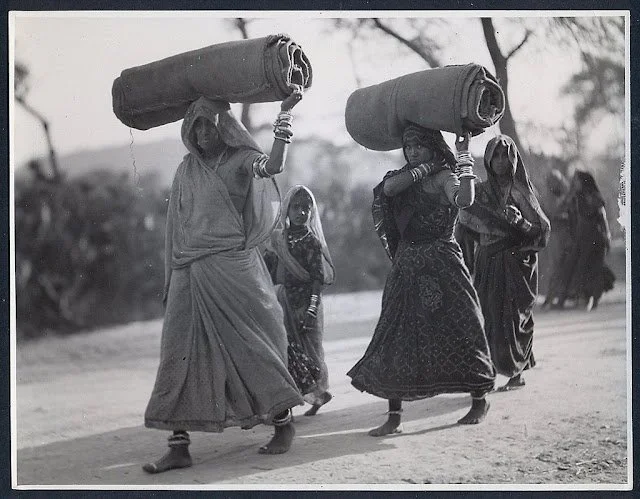

“A Thief Has Come” is a Rajasthani proverb uttered when a girl is born. Throughout their lives, many Indian women face entrenched subjugation.

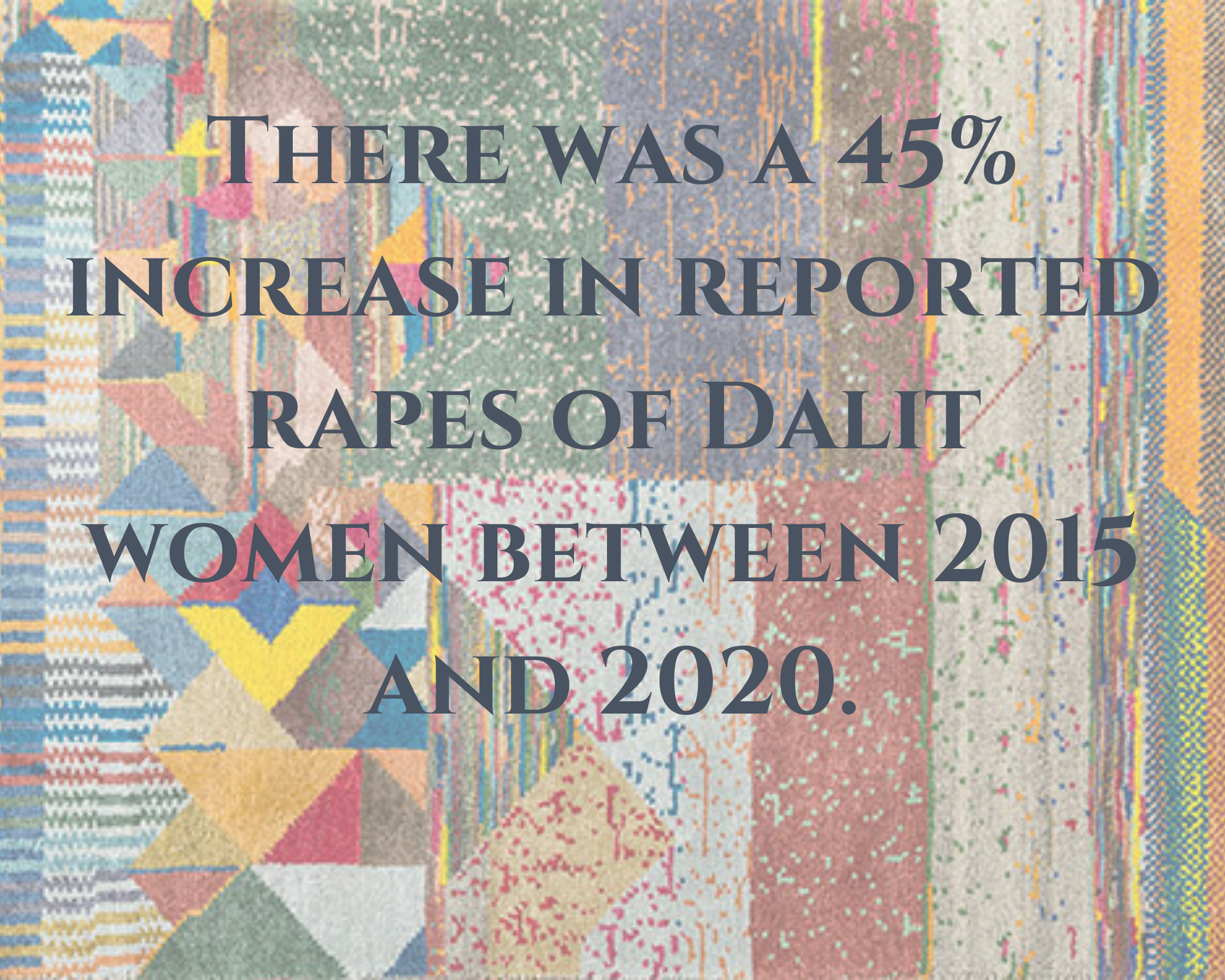

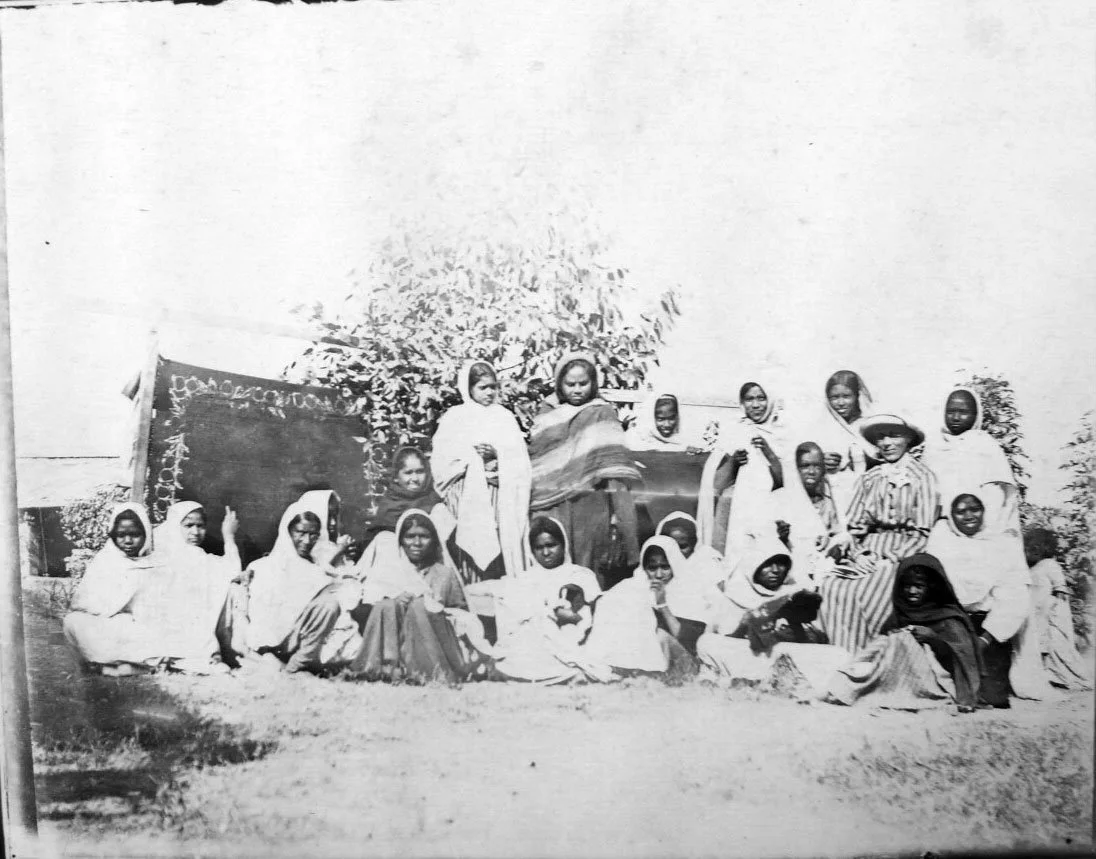

This project reflects upon my collaboration with Jaipur Rugs, a foundation established to train Dalit women (the lowest caste) to weave. Through photojournalism workshops, I sought to empower women to reclaim their identity.

This rug mixes both mine and the participants’ images and, with the accompanying box, tells the project’s story and explores life in rural Rajasthan.

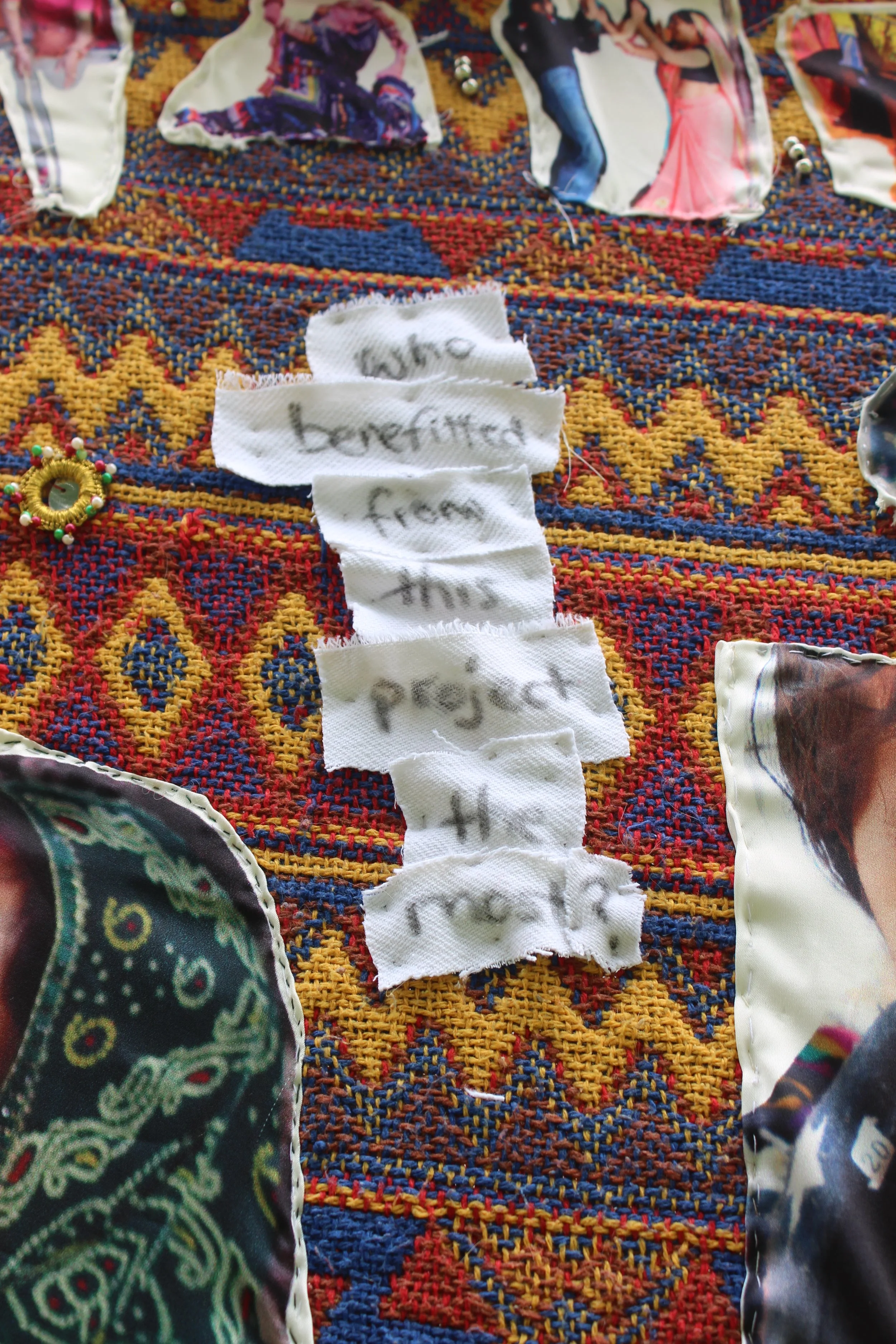

However, this work has raised questions: Who benefited from this? Who owns these images?

A Thief Has Come…is it me?

Read more about my project here.

My Manchaha Rug

The Manchaha is 2.2m wide x 1.4m tall.

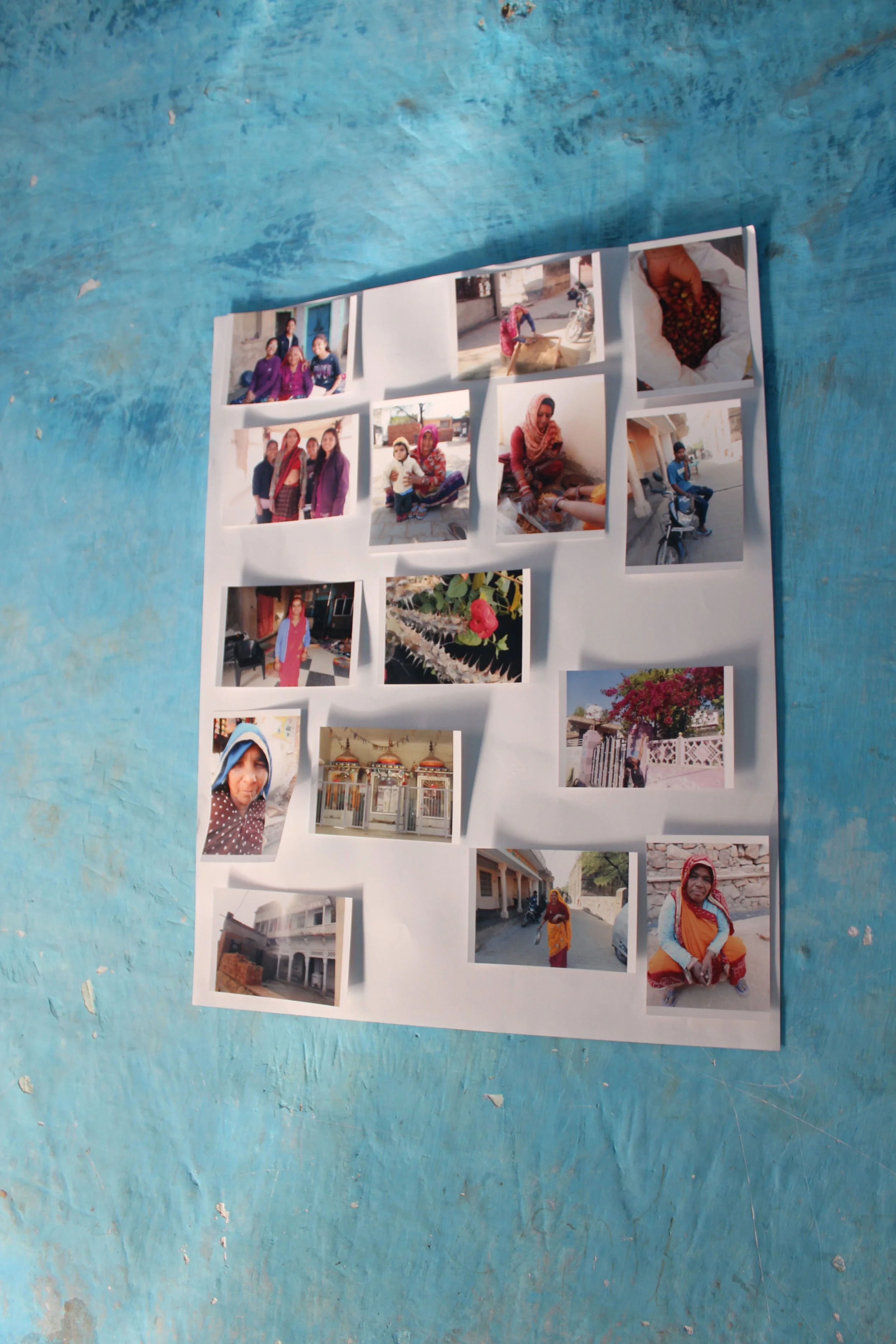

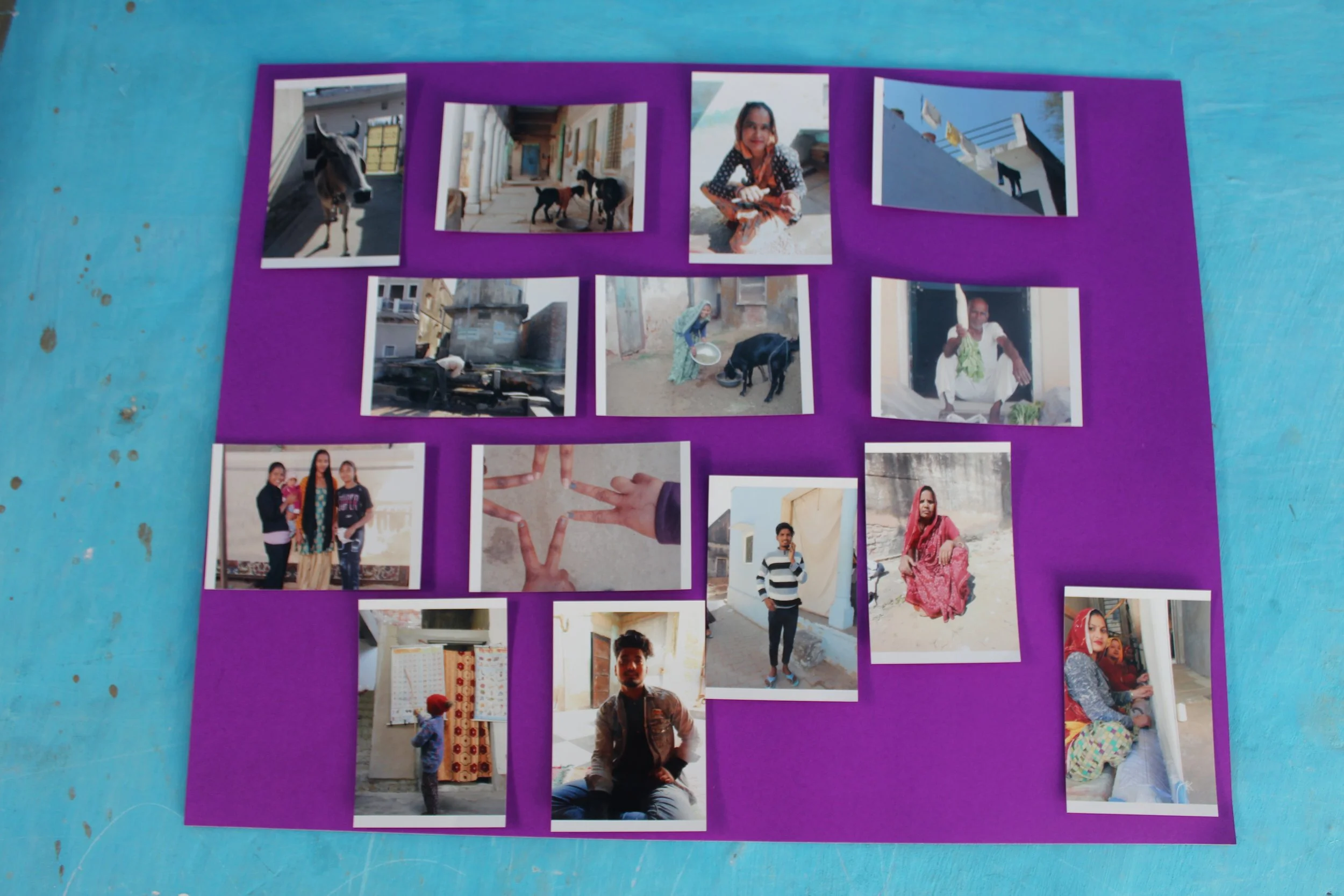

My Manchaha rug has been created by printing both my photos and the participants’ photos onto silk. The individual images have been cut out, hemmed and then sewn onto a larger piece of woven fabric which I obtained whilst in India.

The border of the Manchaha includes miniature photos of Rajasthani women dancing. Indian fabrics often utilise a border of repeated motifs and, as is reflected in my journal entries in the accompanying box, frequently my workshops turned into dance parties. Celebration and dancing is a huge part of Indian culture; as this rug is to pay homage to the weavers of Jaipur Rugs, a border of celebration felt apt.

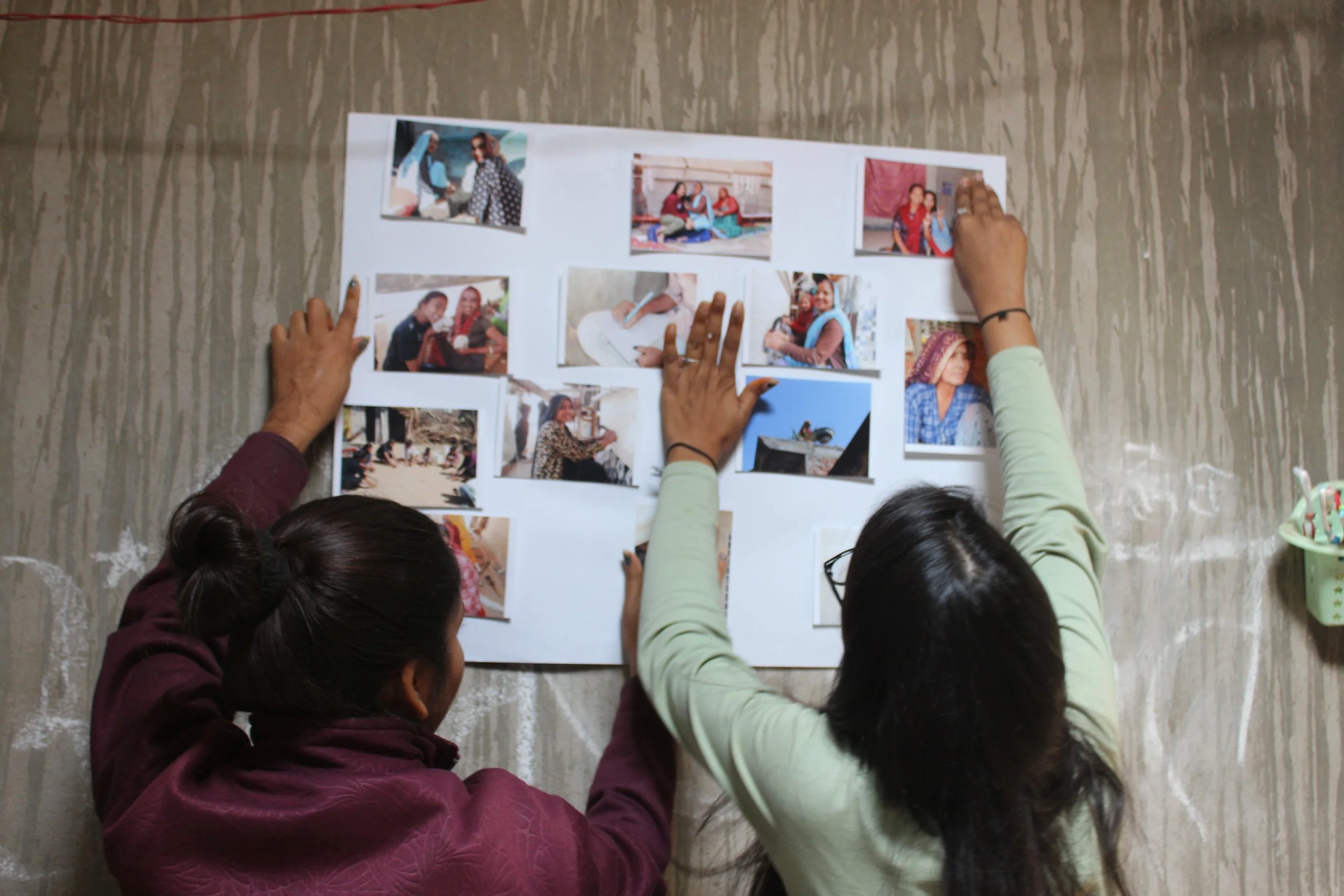

The border is disrupted by three participants looking at the Manchaha. This photograph was taken at one of our project’s pop-up exhibitions; they were viewing and discussing images they had taken.

A map of Rajasthan is in the centre of the rug cut out of a red sheet to show the setting of the project; this has been surrounded by silver beads.

At the centre of this map is a weaver and a loom. Beads are used throughout the rug to separate the dancers in the border. These are sewn in threes, in a traditional Rajasthani custom. There are also typical Indian textile ornaments of mini decorative mirrors scattered in trios across the Manchaha.

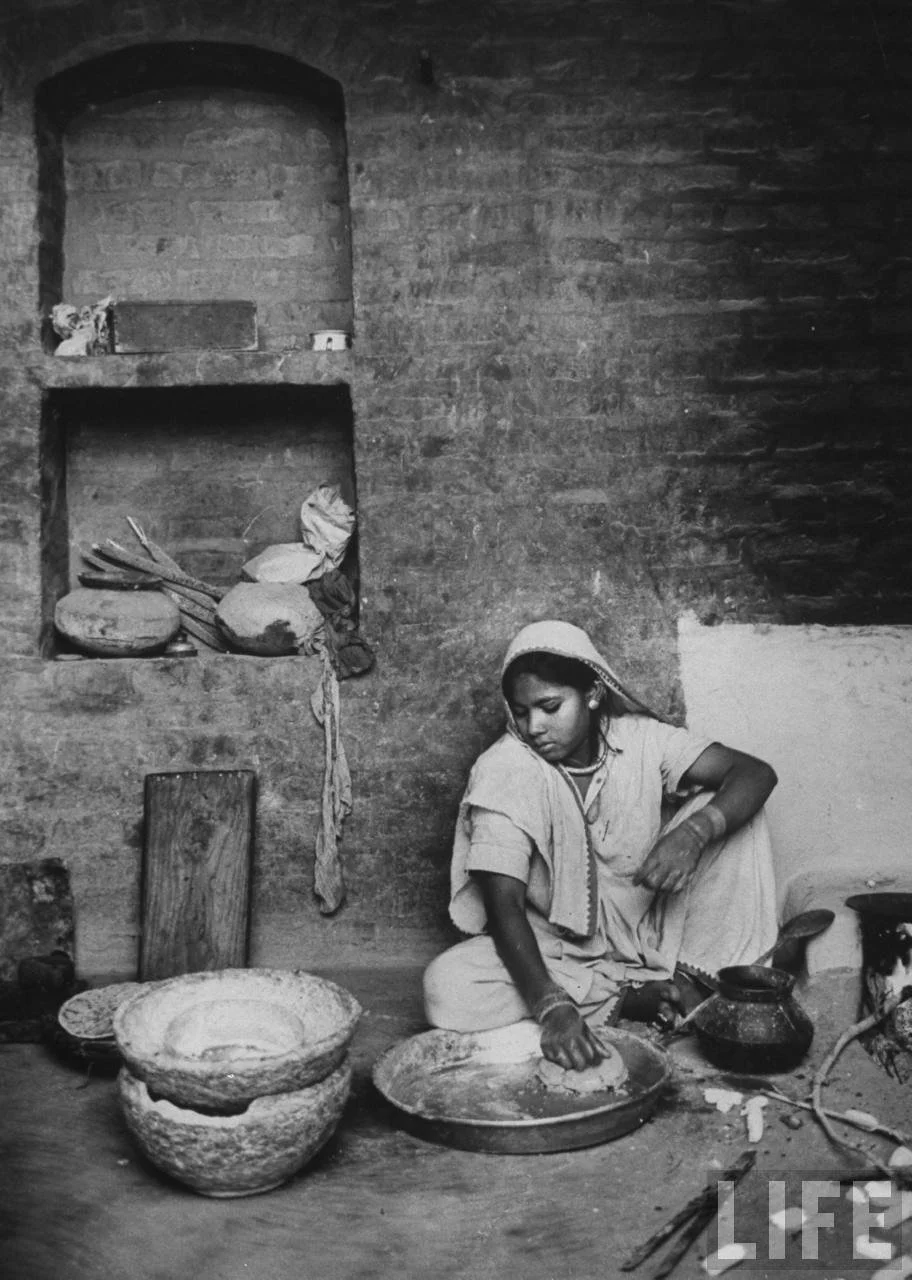

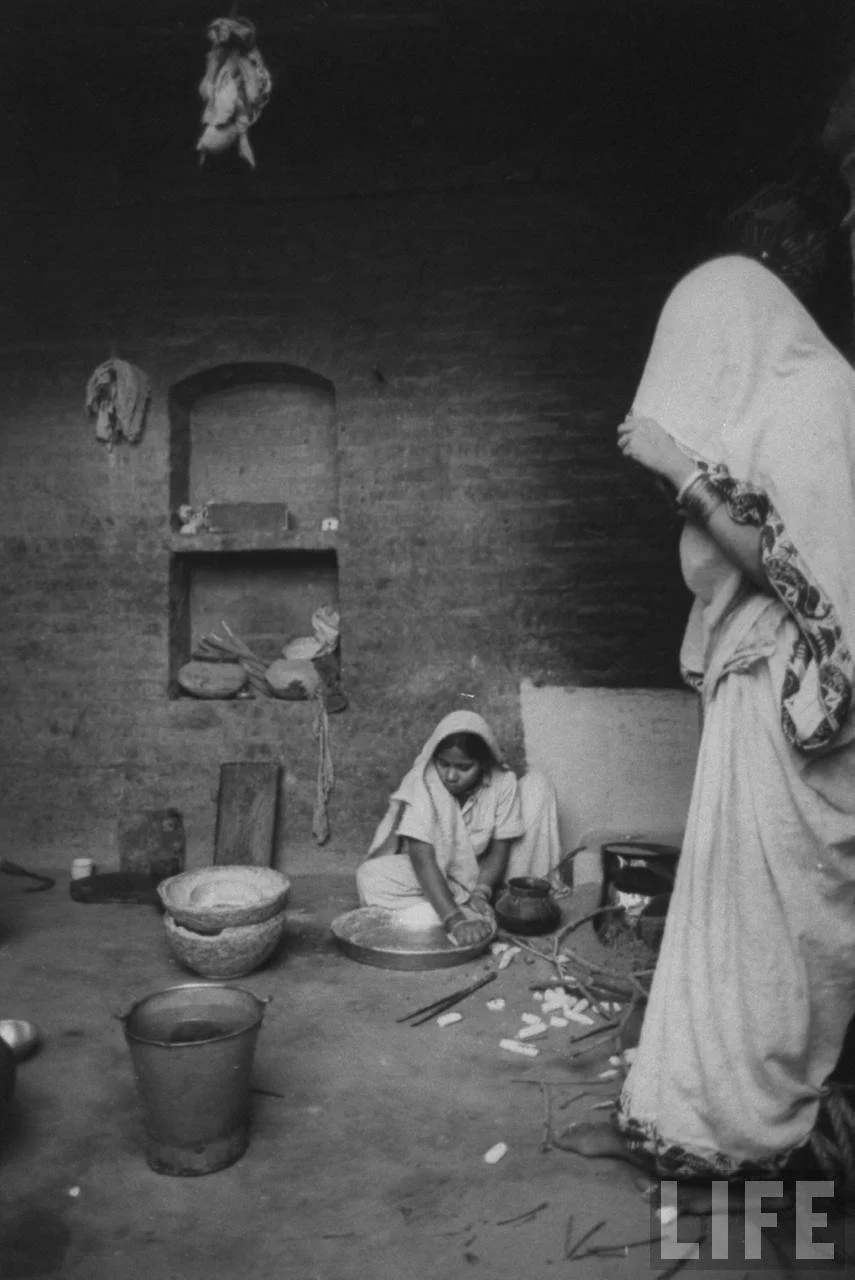

One of the main images of my rug is a large pair of hands decorated with a mehndi in henna ink, instantly showing the Indian setting of the project. Throughout each section of the Manchaha there are images of hands. As well as referring to the hard physical work that the women do, this is a reminder of the “untouchability” of the weavers. There are four main sections to the Manchaha: agriculture; domestic chores; bread; weaving. These were the four subjects that were photographed the most by the participants and were written about most often in their reflections. The women all discussed their routine a lot; each day is typically dictated by tending to animals and crops, cooking, cleaning and weaving. This idea of routine is also a nod to the seminal novel Untouchable. This text, which is included in the box, follows the day in the life of a Dalit man.

Four sections seemed to be the logical number to include; there are four Hindu castes (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Ranjayas, Vaishyas) and four eras of Āśrama (Hindu belief surrounding the stages of life). These four stages of Āśrama are Brahmacharya (child/student 0-25 years old), Gṛhastha (householder, 25-50 years old), Vanaprastha (forest walker/forest dweller, 50-75 years old), and Sannyasa (renunciate, 75 years onwards). These are also reflected in the portraits displayed in the centre of the rug. The ages of the subjects progress following Āśrama in a clockwise direction. This also hints to Hindu beliefs regarding Saṃsāra (the cycle of life, death, reincarnation and rebirth).

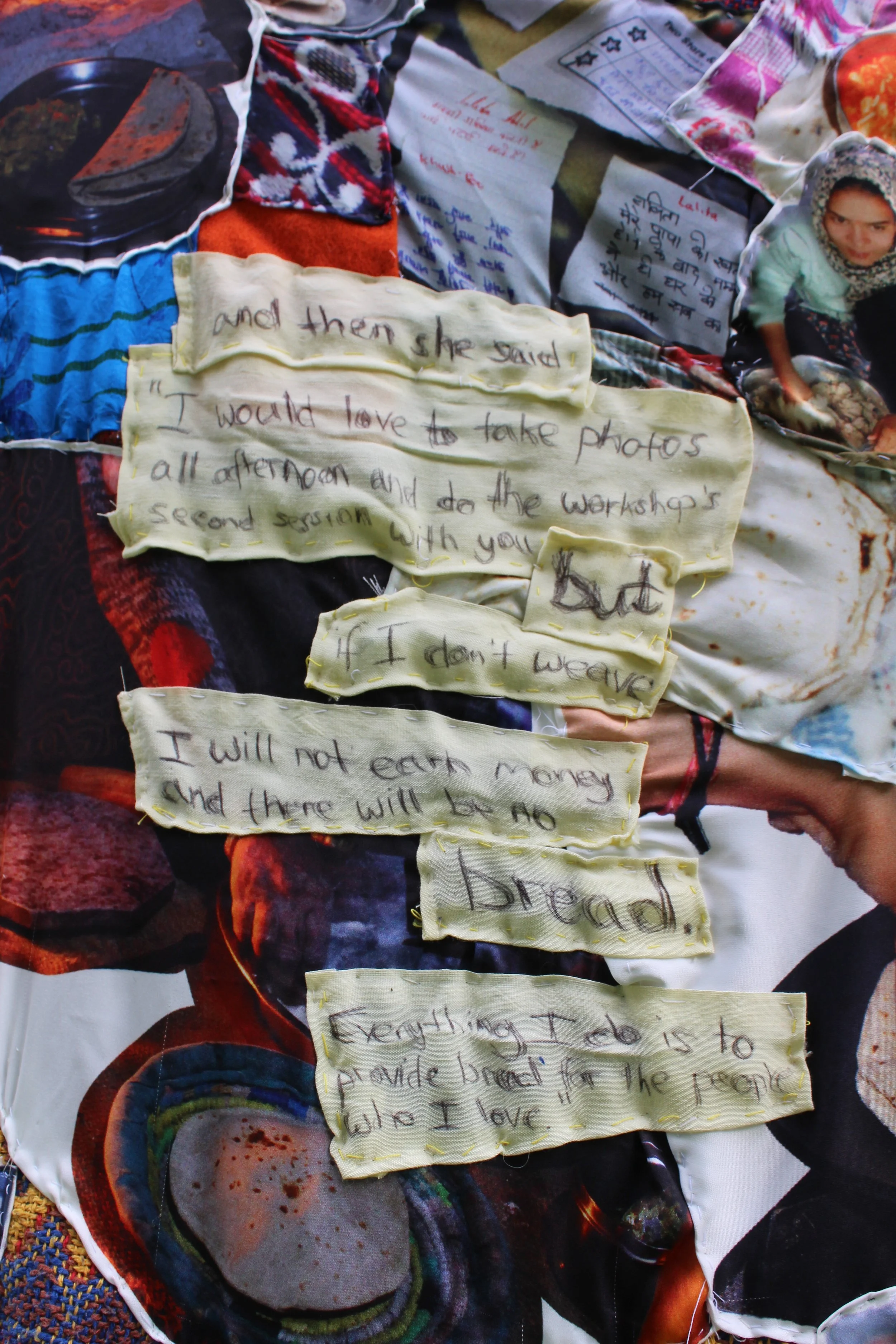

Throughout the rug there are excerpts from my journal written onto cloth, detailing important anecdotes and questions. This is to allude to the difficulties regarding the ethics of collaborative work and a nod to the practical issues that I faced during the project. So as not to make myself the protagonist, thereby stifling the women’s voices further, I have decided to use my critical report as the space to fully examine my stance on this. I also do not wish to be didactic in my opinion on collaborative work; I appreciate that everyone looking at A Thief Has Come will have a different view on the project’s aims, execution and product.

I have also included sections written in Hindi; some of these are from workshop exercises such as “Two Stars & A Wish”, and others are testimonials written

by participants themselves or told to translators. Despite having English translations of these, I have displayed them untranslated in Hindi on the rug so as to have an equal ratio of Hindi to English and no dominant language. I also seek to alienate the English speaking audience by putting them in my position of not understanding. In one workshop, participants were asked to collate any photos or documents they had on phones or in houses of their loved ones. I have collected some of the participants’ favourite found images and, with permission, sewn them on the rug.

There are photos of shoes scattered arbitrarily around the rug; this is reminiscent of my time in the villages. Shoes were removed before entering a house; put on to go to the outside bathroom; removed to walk into the weaving centre; put on to walk down the street etc. This resulted in big piles of shoes, solo slippers and frequent conundrums of flip- flop ownership. This is also reflective of the caste system stance on shoes;

“When entering a village certain norms have to be followed. According to our tradition they [Dalits] are not allowed to walk with their slippers on in the upper caste area.” (India Untouched: Stories of a People Apart. [YouTube.])

At the bottom of the Manchaha, the names of all workshop attendees are listed in alphabetical order. I have not attributed names to images. Partially this is because some participants attended just one or two workshops while others attended many. As the project progressed, cameras were taken back to the homes and workspaces of weavers and swapped; I do not have an exact record of whose image was whose and the participants could also not remember. In both mini exhibitions (details of which can be found in the box), participants were asked if they wanted credit for their images. Universally, all participants said no; they wanted to have them exhibited anonymously and collectively. I have respected this wish in the Manchaha and accompanying box.

The rug hangs from 28 pieces of yarn plaited and together. Each strand symbolises a state of India. The colours of these strands represent the Indian flag (nine orange, nine white, nine green and one navy).

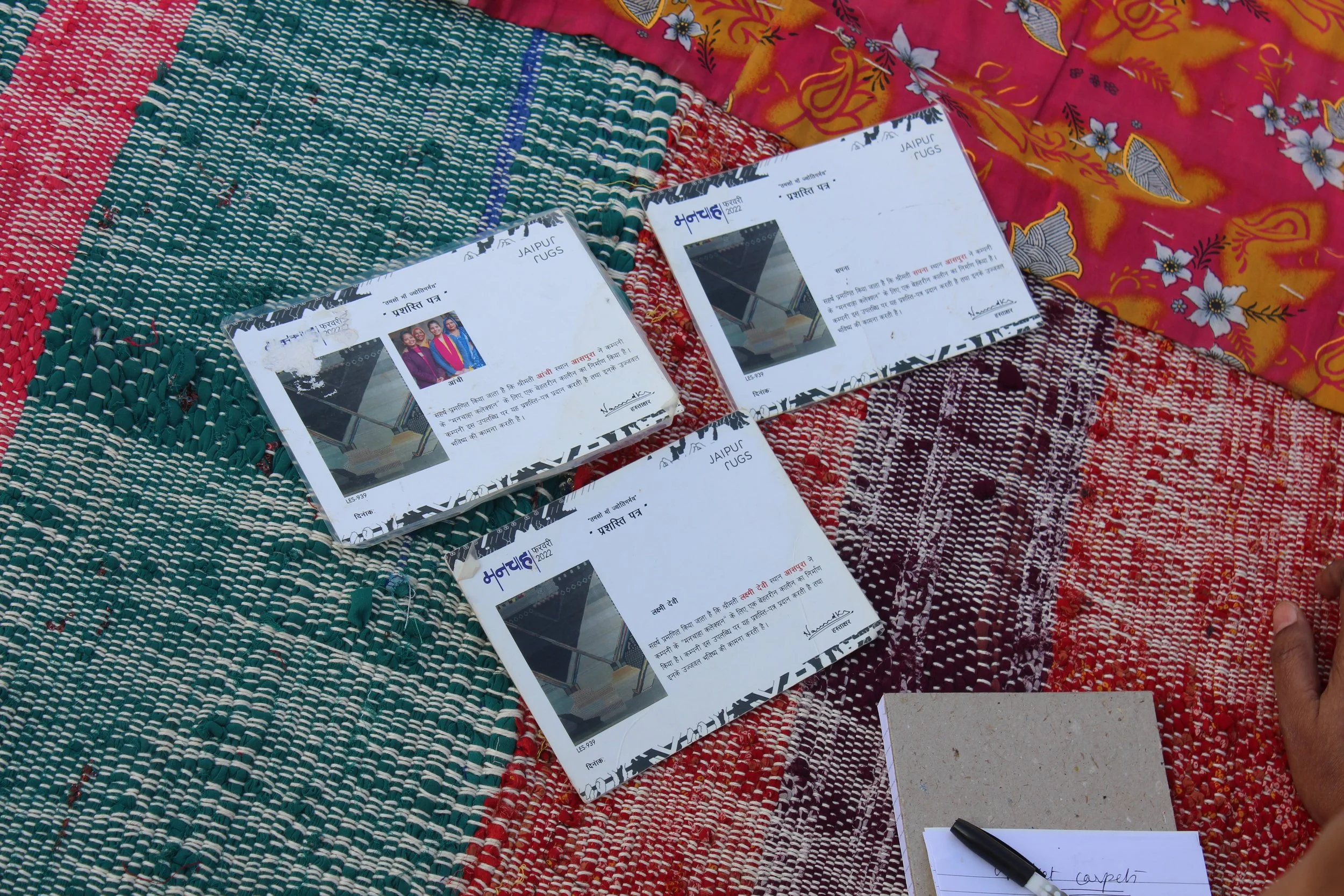

Explaining the box

Throughout my stays in Manpura and Aspura, women frequently took me to their homes and showed a box of prized possessions which inspired their creations.

The rug, which hangs on the wall, is accompanied with a box of work and mementos that influenced my project. To refute the participants’ ‘untouchability’, exhibition attendees are encouraged to explore this through touch, as well as sight.